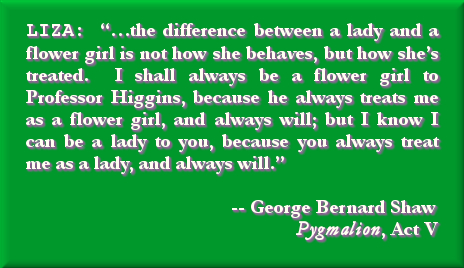

Well, Eliza, old thing, you said a mouthful with that one, didn’t you?

This is one of my favorite quotes from George Bernard Shaw’s witty, wise, and completely charming 1912 comedy, Pygmalion. If you know Miss Doolittle only from the story’s musical version, My Fair Lady — magnificent as it is — you’ve missed a little something of Eliza’s true nature. In Pygmalion, she’s somewhat more spunky, a bit more self-possessed, especially in the end, than the creators of the musical, who romanticized things a trifle more, allowed her to be.

This quote, more or less in identical form, appears in both versions of the story. And, to me, it’s pretty much the crux of the play’s message. Eliza delivers this seemingly gentle speech to Col. Pickering, the colleague of Professor Henry Higgins, who has helped to teach Eliza to “walk and talk and act like a lady”. The occasion is the morning after she has pulled off the feat of appearing as a perfect and somewhat mysterious lady of regal bearing and high standing in front of the cream of London society, belying her roots as a Cockney flower seller. Eliza genuinely means what she is saying to Pickering, whom she holds in esteem, but she’s also tossing a barb over her shoulder at Higgins, who is in the room, too. (Eliza has left the home of Higgins and Pickering after they rudely and cruelly ignored completely her part of the accomplishment and have taken sole credit for her success. She has retreated to the home of Mrs. Higgins, the professor’s mother.)

Shortly after this quote, Eliza asks Pickering, who has always addressed her as “Miss Doolittle”, to call her by her first name. “And I should like Professor Higgins to call me Miss Doolittle,” she adds, batting a line drive straight at the ego of the professor, who has presumptuously always addressed her only as “Eliza”. Pickering graciously accepts the offer of a more intimate friendship; Higgins explodes with anger.

After a frank conversation between the two later in the act, Eliza sets out to attend her father’s wedding, saying to Higgins, “I shall not see you again, Professor. Good bye.” Higgins is, at least outwardly, unfazed, declaring to his mother that Eliza will be back soon enough to take on the role of servant to his every whim. He’s made clear earlier in the act that he thinks she will do this because, basically, she knows no better:

“You call me a brute because you couldn’t buy a claim on me by fetching my slippers and finding my spectacles. You were a fool: I think a woman fetching a man’s slippers is a disgusting sight: did I ever fetch your slippers? I think a good deal more of you for throwing them in my face. No use slaving for me and then saying you want to be cared for: who cares for a slave? If you come back, come back for the sake of good fellowship; for you’ll get nothing else. . . . and if you dare to set up your little dog’s tricks of fetching and carrying slippers against my creation of a Duchess Eliza, I’ll slam the door in your silly face.”

Henry’s not all bad. A pompous ass at times, yes, but not necessarily bad. When Eliza states firmly that she can do without him, he replies, “I know you can. I told you you could.” He concedes, albeit roughly, her right to choose her course: “I go my way and do my work without caring twopence what happens to either of us. I am not intimidated, like your father and your stepmother. So you can come back or go to the devil: which you please.” Henry asserts his independence and principles glibly: although by his own admission he’s fond of her and has “grown accustomed to your voice and appearance”, “I don’t and won’t trade in affection.”

Higgins is certainly confident in himself and his understandings of the ways of the world. He also seems very certain of his understanding of a woman like Eliza and her possible choices in the world they inhabit. He rages against the possibilities of her marrying Freddy Eynsford Hill, the callow gentleman who was bowled over by Eliza’s charms the first time he met her and who now, according to Eliza, loves her.

Yet, for all his bravado, Higgins is neither fully aware of all of Eliza’s options nor of her intelligence. His certainty that she’ll settle for being his drudge because she’s unable to figure out anything else to do is arrogant and ugly.

If Henry is not fully aware of Eliza’s options, she certainly isn’t either at this point. She realizes that she’s been changed, irrevocably, through her training under Higgins and Pickering. She’s now a “lady” and this isn’t necessarily a blessing as she sees it at present. The evening before — now that the task of making her appear a certain way has been accomplished— she has cried out: “What am I fit for? What have you left me fit for? Where am I to go? What am I to do? What’s to become of me?”

In the final act (V), Higgins assures her that his mother could probably set her up with some man in a marriage to a prominent individual. Eliza bolts at the idea, seeing it as little more than prostitution, affirming that she was always above that sort of thing even in her most penniless days: “I sold flowers. I didn’t sell myself. Now you’ve made a lady of me I’m not fit to sell anything else. I wish you’d left me where you found me.”

Indeed, what has happened to Eliza now that she’s fit for “society”—now that, by outward appearance and manner of speech, she’s a “lady”? She’s lost something. Something she always had previously. Let’s let her say it:

“Oh! if I only could go back to my flower basket! I should be independent of both you and father and all the world! Why did you take my independence from me? Why did I give it up? I’m a slave now, for all my fine clothes.”

In the musical version of the story, My Fair Lady, Eliza does indeed come back to Higgins in the end, carrying his slippers. But we’re led to believe, through the further development of Higgins’s character in the final musical number, that realizing his love for Eliza, he has changed. And that Eliza’s choice is something of a victory for her: She knew all the while how he really felt and that she would, therefore, capitulate—not from necessity, but by clear-headed choice. She just needed to prove to him first that she could and would leave him, that they were, indeed, equals.

That’s lovely but it’s not Pygmalion. It’s more Candida, another pleasant, if somewhat bittersweet comedy, also by Shaw from a few years earlier. The characters in that one, though, are a little different. Candida is from a fairly different background than our Eliza and, while a lady, hasn’t been elevated to quite the ranks that Eliza has. There’s no illusion that she might be a duchess. She’s the wife of a clergyman and when asked to choose between her husband, who can also be about as infuriatingly pompous as Higgins, and a young romantic suitor, who thinks she’s living a life beneath her dignity, makes clear to the suitor and her husband that she’s fully in charge. “I make him master here!” she boldly proclaims. Without her and her choice to support him and see to some of the less glamorous tasks of their lives, he would be nothing. And Candida knows it all the time.

So maybe it’s more Candida who comes back to Higgins at the end of My Fair Lady than Eliza. Certainly Shaw, himself, thought so. In an afterword published with the play (‘though not as part of the script and not written in play form), Shaw makes clear that Eliza will never stoop to marrying a man who doesn’t love her, as he says Henry does not and cannot. She’s much too wise and independent a person for that, with a much brighter future than even she knows at the end of the play.

Shaw’s thoughts certainly make Eliza a more “modern” and “liberated” character. The musical’s ending may make her more mature, though, especially in the knowledge of what love’s all about.

The final act of Pygmalion as written, though, (without Shaw’s later musings) makes for a deliciously ambiguous and thought-provoking ending that keeps audiences engaged long after the curtain has rung down.

And how does all this relate to our work at The Earl Wentz and William Watkins Foundation? Well, that’s for a post the next time out….Stay tuned!

You are a great writer.

Hello mates, pleasant paragraph and good urging commented here.

I am truly enjoying by these.