Photo credit: William Watkins, 2014

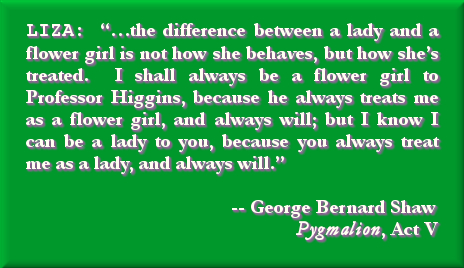

In our post on November 22, 2014, “Of Flower Girls and Ladies — Part I”, we delved into a quote from George Bernard Shaw’s “Pygmalion”, spoken by the heroine, Eliza Doolittle:

“. . . the difference between a lady and a flower girl is not how she behaves, but how she’s treated. I shall always be a flower girl to Professor Higgins, because he always treats me as a flower girl, and always will; but I know I can be a lady to you, because you always treat me as a lady, and always will.”

We explored how this central theme played out in the characters’ behavior throughout the play (as well as in its musicalization, “My Fair Lady”) and its implications, once Eliza realizes the truth of it, particularly for her independence and for her future.

We left by asking how all of that relates to the work of The Earl Wentz and William Watkins Foundation. It’s there that we pick up today.

If you haven’t read Part I, you may want to do that by clicking on this link before reading on.

________________________________________________________________________

Despite a marvelously nuanced performance by Rex Harrison in both the stage and film versions of My Fair Lady, where we see the heart of Henry Higgins start to melt before our eyes and thereby transform the exterior blustering beast as Higgins realizes that much to his consternation, he has “grown accustomed to” Eliza’s face, this Higgins is not that of Pygmalion either. Higgins arrogantly proclaims in the musical that he has made a woman of Eliza, but it is she who has actually made a grown man of him. It’s utterly charming here and delicious fodder for those with romantic appetites but it isn’t totally what the original author, George Bernard Shaw, intended.

In Pygmalion, Higgins doesn’t really understand what Eliza is so upset about on the morning after her triumph. He certainly can’t understand why, in exasperation, she has thrown his slippers in his face: “She behaved in the most outrageous way. I never gave her the slightest provocation.” It is for his mother, Mrs. Higgins, to begin the explanation: “She worked very hard for you, Henry! . . . . it seems that when the great day of trial came, and she did this wonderful thing for you without making a single mistake, you two sat there and never said a word to her, but talked together of how glad you were that it was all over . . . . and how you had been bored with the whole thing.” She continues, telling him what he really deserved: “And then you were surprised because she threw your slippers at you! I should have thrown the fire-irons at you.”

Continue reading Of Flower Girls and Ladies — Part II →